3 global shifts reshaping markets

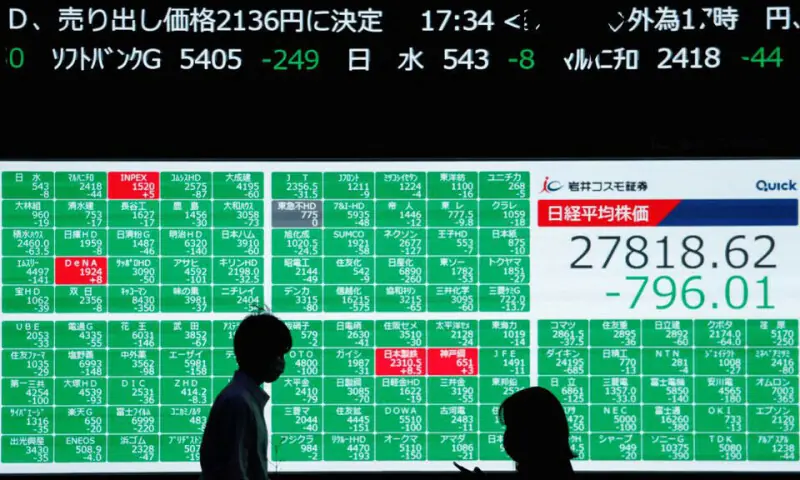

Global markets tend to shift long before anyone notices. A small tremor turns into a fault line, and what feels stable can give way without warning. Three such changes are now forming beneath the surface, in Japan, in Washington and across Europe, each with the potential to reshape policy, flows and currencies in the months ahead. Japan: a storm building in silence The entire world is borrowing yen at 0.5 per cent and earning $4. It looks calm. It feels stable. But this is the most vulnerable structure in global liquidity today. The moment Japan hints at tightening, that calm will break. As the US Federal Reserve System (Fed) eases interest rate and the Bank of Japan tightens, guess what happens to the yen against the dollar? The pace at which carry trades unwind will throw all cross assets into stress. Japanese institutions have been selling US T-bills, a trend that can accelerate as hedging costs rise and the economics of the carry trade break down. Add to this a Japan that is finally opening its doors to global capital, including the Gulf Cooperation Council, rebuilding its buyout market, and inviting investment into artificial intelligence, defence and advanced manufacturing. Japan is pivoting. And markets are not prepared for how quickly the yen can move once the Bank of Japan shifts its stance. Traders believe the State Bank will buy surplus dollars to rebuild reserves, limiting further appreciation and keeping the currency close to current levels. The Fed: a shift beneath the surface As expected, the US Federal Reserve has cut rates by 25bps, but not without three dissents. The question is what happens after this? Political pressure on the Fed is rising. The question is not whether Jerome Powell, Chair of the US Federal Reserve, cuts once or thrice next year; the question is who will shape the Fed’s direction over the next two years. Monetary policy only works when the institution is seen as independent. Right now, that anchor is under strain. Disinflation is progressing. Labour softening is clearer once you strip out noise. But markets are no longer just reacting to data. They are reacting to the possibility that the Fed may become an extension of the White House rather than an independent institution of monetary regulation. It is subtle, but it is seismic. Europe: a fault line The new US National Security Strategy unsettled the foundation of the trans-Atlantic relationship. The strongest criticism was aimed not at Russia or China but at Europe itself. It described European governments as weakened and struggling to hold identity. This is a written policy, not an offhand comment. It also recasts the US as an intermediary between Europe and Russia rather than Europe’s anchor. For markets, this adds a long-lasting political risk premium at a moment when the European Central Bank cannot afford it. Currency outlooks Pakistan finally secured the $1.2 billion facility under the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) Extended Fund Facility and Resilience and Sustainability Facility. Country reserves should move past the $20.5bn mark, a level last seen during Covid-19, and that alone is keeping sentiment steady. Interbank liquidity is calm, nostros are comfortable, and the market is now asking if the rupee can stretch toward Rs278 per dollar. Trade flows do favour levels below Rs280 per dollar, but traders’ view is that the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) will step in to buy excess dollars and rebuild reserves rather than allow further appreciation, keeping the currency close to current levels. Data from October also shows SBP’s net short swap position holding near $2bn, so the pressure on forward premiums is coming from exporters selling forward and a rise in foreign exchange loans, not from any change in the SBP’s stance. However, we expect premiums to improve marginally now that IMF dollars are received. As for the Indian rupee (INR) slipping past 90 per dollar, it was less about the number and more about the silence that followed. For the first time in years, the market sensed that the Reserve Bank of India was willing to let the rupee breathe on the downside. No dramatic defence or heavy selling, but rather an uneasy acceptance of the new level. The INR will not likely find any respite from the 25bps Fed rate cut. For the INR to stabilise, it needs two structural shifts: an oil bear market that resets India’s terms of trade and a US–India trade deal that finally unlocks the next leg of growth. Until then, it will drift further into the early 90s. It is a currency in waiting, not a currency in crisis. Finally, the Great British Pound rallies feel like echoes of an older world; they do not last. Each bounce runs into the same issues: political noise, fragile gilts, and conflicting policy signals. Sterling is not broken, but it no longer has the cushion it once enjoyed. For now, strength invites selling more than commitment on the buy side. Faisal Mamsa is CEO of financial market data platform Tresmark. Published in Dawn, The Business and Finance Weekly, December 15th, 2025