Tennessee whistleblower says library board chair sought private data as part of state's book purge

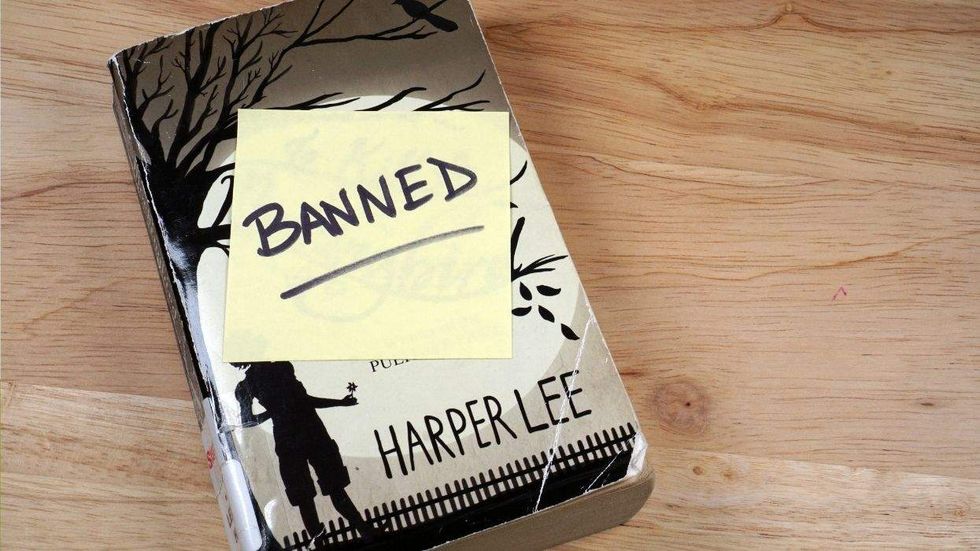

On the first night of December in Rutherford County, Tennessee , a newly hired library director stood before her governing board and did something almost unheard of in American public librarianship: She asked for whistleblower protection. Keep up with the latest in LGBTQ + news and politics. Sign up for The Advocate's email newsletter. Luanne James had taken the job at the end of July, uprooting her family to lead a suburban library system outside Nashville. Now, she told the board, she feared retaliation. She accused the board chair of directing her to pull books from shelves and to compile data on who’s been checking them out. According to advocates who attended the meeting, James said the chair of the library board, Cody York, who is also the county’s chief information officer, had demanded, just days after she arrived, that she produce a spreadsheet listing patrons’ names, home addresses, ZIP codes, household composition, and the specific books they had checked out. More than 50 residents rallied outside Murfreesboro City Hall, many holding American Civil Liberties Union signs urging Tennessee to “protect the freedom to read.” Inside, the crowd spilled into the aisles as James laid out her concerns, as detailed by the Daily News Journal : In addition to requesting patron data, she said York discouraged the system from participating in Banned Books Week and showed her books he had taken from the shelves without returning. Related: Bombshell records expose political plot to oust rural Georgia librarian over LGBTQ+ book James’s plea unfolded in front of a community already roiled by weeks of turmoil. That pressure had been building for months, as the Rutherford County Library Board cycled through repeated battles over whether to remove books addressing gender identity and LGBTQ+ themes. Earlier efforts to pull titles were met with protests and legal warnings, prompting the board at one point to reverse course over fears of First Amendment litigation, only to return to the issue again as new state directives tied library oversight to Trump-era language about “gender ideology,” reopening long-simmering disputes over censorship, governance, and the role of public libraries. A motion to remove York followed James’s complaint of misconduct during the meeting. After board member Allison Belt asked James to describe her allegations, she, joined by board member Angela Frederick, called for a vote to remove him as chair. In a 7–2 decision, the board declined to do so. York abstained. The results prompted frustration among many in attendance and deepened opponents’ sense that ideological forces had captured the system. Outside, protesters, some at their first demonstration, lingered in the cold, voicing a sentiment repeated across the state: “Just don’t ban the books.” York rejected the accusations, according to Nashville Fox affiliate WZTV. “I deny completely any wrongdoing,” he said at the December 1 meeting. Related: Beloved Georgia librarian fired after child chooses book with transgender character for library display However, during a meeting in March, before York became chairman, he called for the board to “remove material that promotes, encourages, advocates for or normalizes transgenderism or ‘gender confusion’ in minors." Neither York nor James responded to The Advocate’s request for comment. To librarians and civil liberties advocates, with whom The Advocate spoke, the request landed like a thunderclap. It was not merely inappropriate. It struck at one of the oldest and most fiercely protected principles in American library ethics: that what people read in a public library belongs to them alone. That meeting’s developments marked a new and dangerous phase in a conflict that has been quietly building for years in Rutherford County and now threatens to become a national test case for how far government power can reach into public libraries under the banner of ideology. A warning letter in September On September 8, Republican Tennessee Secretary of State Tre Hargett sent a statewide letter to library directors reminding them that federal grants administered by the Tennessee State Library & Archives could not be used “to promote gender ideology,” citing one of President Donald Trump’s executive orders targeting what it labels “gender ideology.” The order itself does not mention libraries. In the letter, Hargett reproduced verbatim the executive order’s definition of “gender ideology,” describing it as an ideology that “replaces the biological category of sex with an ever-shifting concept of self-assessed gender identity… and maintains that it is possible for a person to be born in the wrong sexed body.” Related: Georgia Senate passes bill banning American Library Association from state libraries He cautioned that libraries “must be mindful of the requirements of state and federal law,” and linked the warning to Tennessee’s new Dismantling DEI Departments Act, which restricts local governments from using “discriminatory preferences to promote diversity, equity, or inclusion.” In effect, the September letter established the ideological lens through which Tennessee would soon view public library collections. Next, Hargett sent formal letters, which The Advocate obtained, to the Linebaugh Public Library on October 27, which included York and Smyrna Public Library Director Cassandra Taylor on October 31, which also included York, ordering Rutherford County libraries to begin an “immediate age-appropriateness review” of all juvenile materials over the next 60 days. The directive required boards to initiate reconsideration proceedings for any titles they believed violated state or federal law and to submit final reports by January 19, detailing which books were deemed inappropriate and what actions were taken. “I cannot allow the actions of one library to potentially harm and impact over 200 other libraries throughout the state,” Hargett wrote. Across the Tennessee Regional Library System — 211 libraries in 91 of 95 counties — it was interpreted as a green light for mass ideological audits. Related: Virginia Republicans vote to take control of local library after losing fight to remove LGBTQ+ books In Rutherford County, two branches temporarily closed in November so staff could review nearly 60,000 books. More than 2,400 titles were pulled for further evaluation. The county also adopted an opt-out “graduated” library card system that bars minors from accessing adult nonfiction and reference materials, including SAT prep guides, unless a parent appears in person. To supporters, it was about parental rights and child protection. To critics, it looked like a blunt force ideological purge. Hargett did not respond to The Advocate’s request for comment. “This isn’t about obscenity,” Keri Lambert, vice president of the Rutherford County Library Alliance, told The Advocate in an interview. “This is about eliminating the acknowledgment that LGBTQ+ people exist.” Viewpoint-based removals are unconstitutional Within weeks of Hargett’s directive, the National Coalition Against Censorship sent a sharply worded legal warning to the Rutherford County Library Board. In its December 1 letter , NCAC reminded board members that “the First Amendment prevents a library from making viewpoint-based removals and trumps any federal or state law to the contrary.” Related: How library workers are defending books, democracy, and queer lives The group emphasized that even when government officials control funding, their discretion is “particularly limited” when it comes to removing books, and may not be exercised in a “narrowly partisan or political manner.” The coalition also dismantled Hargett’s reliance on Trump’s executive order, writing that executive orders have force only within the federal executive branch and “have no force of law as impacting the state of Tennessee.” It noted that multiple federal courts have already enjoined portions of related executive orders as unconstitutional viewpoint discrimination. “Given the tenuous legal status of the order,” the coalition warned, “library boards should be disinclined to remove books pursuant to its unclear and likely unconstitutional requirements.” A board rewritten Lambert traces the conflict around books in the state back to 2023, when a local “decency ordinance,” widely criticized as anti-LGBTQ+, briefly took effect in 2023 Murfreesboro before being rescinded in 2024. The ordinance banned “indecent behavior” considered “harmful to minors”. The policy, which included “sexual contact” and “sexual acts,” defined homosexuality as a sexual act. That fight, she said, ignited a years-long campaign to capture the library board itself. “They didn’t give up after the ordinance failed,” Lambert said. “They pivoted. And they went straight for the libraries.” She says York later became board chair after promising to rewrite policies “to ensure none of that so-called ‘filth’ stayed in our libraries.” Shortly afterward, long-standing board responsibilities, including adherence to the American Library Association’s Freedom to Read principles, were quietly removed from official policy documents, Lambert said. Related: Southern states ban transgender books from YA and children's sections in libraries What followed, advocates say, was a cascade of book challenges. Around the country, these kinds of attacks on the freedom to read have often been initiated by a single individual, often focused on LGBTQ+ content, and rarely grounded in professional review standards. “These books are not being reviewed by librarians,” Tatiana Silvas, the alliance’s communications director, told The Advocate . “They’re being reviewed by board members with no training, no degrees, and no criteria—only their personal agendas.” Among the books pulled were a Thanksgiving picture book that includes two dads in an illustration and Making a Baby , a board book explaining adoption and IVF alongside pregnancy, Silvas explained. People are shocked when they learn that, Silvas said. “They assume it’s pornography. It’s not. It’s representation. It’s health . It’s reality.” Huge potential constitutional issues The American Library Association condemned Tennessee’s directive. “There are already laws regulating legal obscenity, and there are no legally obscene materials in public libraries,” the organization said in a statement to The Advocate . “The Secretary of State’s letter is unclear in its criteria and standards by which materials are to be evaluated. It also references EO 14168, which does not reference libraries and is facing numerous challenges in the courts.” The ALA warned that vague censorship laws across the country have already triggered expensive lawsuits and said Tennessee communities risk the same fate. “These expenses come out of taxpayers’ pockets and impact libraries’ abilities to provide vital services,” the statement said. For First Amendment scholars, the constitutional stakes are even more severe. “Libraries are usually considered ‘limited’ public forums, which means the government may audit the contents of what’s in a library consistent with the purpose of opening up a public library (presumably, to provide public access to knowledge and literature),” Francesca Procaccini, an associate professor of law at Vanderbilt University, told The Advocate . “So if the audit is for the purposes of ensuring the collection furthers this purpose, that is ok. The government may never limit or regulate speech in a limited public forum for ideology or viewpoint, however.” On the mechanics of power inside the system — political appointees overriding professional staff — she noted that courts are “generally permissive of government boards [or] officials overriding subordinate public employee decisions, even if the subordinate’s decision implicates First Amendment concerns,” so long as the decision falls within the employee’s job duties. But the county’s “graduated” card system, she said, raises distinct constitutional problems that go beyond parental opt-out policies. “The two are distinct,” Procaccini said. “Parental opt-out rights are different because these rights stem from the parents’ own First and Fourteenth Amendment rights,” to speech, religion, and to raise their children. “Here, the graduated card system seems to implicate the children’s own constitutional rights.” She explained that the U.S. Supreme Court has ruled that “children have First Amendment rights and that prohibiting their access to expressive content, even if the law allows a parent to override the ban, is unconstitutional.” Procaccini added that while a court might treat a public library somewhat like a school, precedent still offers little comfort to censors. “The Court said that even public school libraries can’t remove books on the basis of ideology,” she said. “So either way, the graduated card system raises serious First Amendment problems.” Asked about the demand for patron identities and checkout histories, Procaccini sounded the alarm. “Huge ones!” she said, referring to the legal implications. “You have to go back to the 1950s for the most relevant cases, but the Court has been clear then and since that compelled disclosure of expressive association where there is no legitimate governmental purpose or a risk of persecution from disclosure is unconstitutional.” Procaccini placed Tennessee’s fight firmly in a national pattern. “It’s part and parcel of a national effort to influence culture through the suppression of knowledge, educational materials, and dissenting or differing viewpoints,” she said, adding that what is new is “how national the efforts have become, coordinated and supported by national parties and organizations, and how courts seem to be increasingly tolerating the suppression of diverse viewpoints, as evidenced by recent cases like Mahmoud v. Taylor and Little v. Llano . This year, the Supreme Court’s decisions in Mahmoud v. Taylor and Little v. Llano deepened those concerns: in Mahmoud , the Court expanded parental opt-out rights in a case involving LGBTQ-inclusive storybooks, and in Little , it declined to hear an appeal over the removal of books from a Texas public library, letting stand a ruling that permitted officials to purge titles without violating the First Amendment. A national campaign against books For PEN America, which tracks book bans nationwide, Tennessee is now a convergence point. “This is a further escalation,” Kasey Meehan, the group’s Freedom to Read program director, told The Advocate . “You now have legislative pressure, political pressure, and administrative pressure all converging on public libraries at once.” Meehan said what is unfolding in Tennessee reflects patterns PEN has documented nationally, where “a handful of individuals exert outsized influence” over book challenges despite presenting themselves as representing broad community sentiment. She noted that research repeatedly shows these disputes are “rarely organic,” but instead fueled by coordinated networks that recycle identical challenge lists from state to state. She called the reported attempt to obtain patron checkout histories “wildly alarming” and warned such data could be used “to harass, intimidate, or criminalize people.” Meehan said the dynamic places ordinary librarians in impossible positions: “Libraries become ideological battlegrounds, and people are ostracized simply for defending access to books.” What worries her most, she said, is the speed and scale of the shift. Tennessee’s directives, combined with local boards purging titles and rewriting policies, represent “a further escalation of a national campaign that is becoming more coordinated, better resourced, and increasingly aimed at public libraries—not just schools.” The American Civil Liberties Union of Tennessee was also highly critical of the situation in Rutherford County. “The Constitution protects the right of students to access information and ideas, and the right of authors to communicate those ideas without undue government influence. That means the government cannot censor books solely based on dislike of or disagreement with the ideas they contain. Dr. Cathryn Stout, ACLU-TN’s strategic communications director, told The Advocate in a statement. “The Constitution protects the right of students to access information and ideas, and the right of authors to communicate those ideas without undue government influence. That means the government cannot censor books solely based on dislike of or disagreement with the ideas they contain." She added, "By banning books, local library systems, such as Rutherford County’s, aim to erase the culture, history, and ideas that support racial equality and LGBTQIA+ acceptance. Ultimately, the biggest victims if this censorship is allowed will be Tennesseans, who will be deprived of the critical skills necessary to participate in a diverse, dynamic, and pluralistic democracy.” According to local activists, daily library operations in Rutherford County are unraveling. Silvas described leaking roofs, deferred repairs, and staffing shortages—all while thousands of books are being stripped and replaced. “Every book that comes off the shelf has to be repurchased,” she said. “That’s an enormous drain on already thin budgets.” She also warned that the removals weaken child safety. “These books give kids the vocabulary to protect themselves,” she said. “Without them, predators have an easier path.” Frank Lambert, her husband and a library and information science professor at Middle Tennessee State University, said what is happening in Rutherford County reflects a profound misunderstanding of what public libraries are designed to do. In his view, the people now driving policy “are not operating from any professional framework,” and their decisions show “no recognition of library science, constitutional requirements, or even basic collection development principles.” Frank Lambert told The Advocate that the removals are not only ideologically driven but structurally dangerous because they bypass librarians entirely. He warned that allowing political appointees to treat public collections as extensions of personal belief systems sets a precedent that “can swallow the entire purpose of a public library.” According to Lambert, the county’s review process has been so unmoored from professional standards that it has repeatedly flagged books simply for acknowledging LGBTQ people or other marginalized communities — a pattern he described as “erasing lived reality under the guise of protecting children.” He also noted the broader cultural ripple effect: that when libraries purge information under political pressure, entire communities begin to internalize the idea that certain people, identities, or histories are inappropriate for public space. The effect, he said, is not neutrality but “an engineered absence,” one that disproportionately harms young readers who rely on libraries to understand themselves and the world around them. Still, he said he believes the legal system will ultimately reject what is happening in Tennessee. He pointed to past litigation, including a Montana case that resulted in a significant settlement for a librarian fired for refusing to remove books, as evidence that courts have recognized library censorship as a constitutional harm. “The legal precedent is on our side,” he said. “They may win local skirmishes, but the First Amendment has a very long memory.” And he returned to the principle that animates his work as a librarian and educator: freedom of inquiry. “I have no right to tell you what you can read,” Lambert said. “Nobody should have that right.” A test of the right to read Rutherford County Mayor Joe Carr did not respond to a request for comment. Legal challenges appear inevitable. “If this succeeds in Tennessee,” Meehan said, “it will be replicated elsewhere. The question is whether we protect the right to read, or allow public institutions to become tools of ideological enforcement.” For Keri Lambert, the stakes are personal and generational. “When you restrict children’s access to information, you don’t protect them,” she said. “You shrink their world. And once you shrink the world for one group, it never stops there.” Public libraries, she said, were built for the opposite purpose. “They exist so that no one—not a church, not a politician, not a board—gets to decide who deserves access to the truth.”