How Ibne Safi taught an entire generation to read

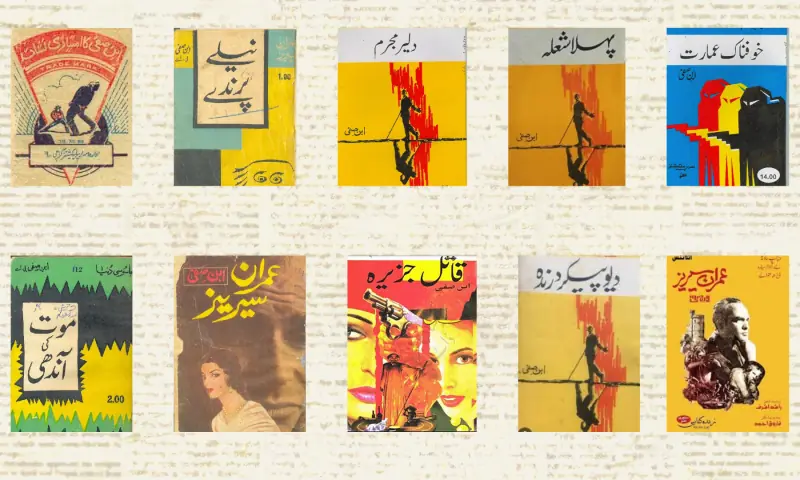

Karachi in the 1950s was not only a city under construction; it was a city learning how to read. The years following Partition brought millions of migrants, anxieties and uncertainties to the port city. Together, they produced something: a wide public hungry for entertainment — gripping stories and dramatic narratives that could momentarily release readers from the grind of everyday survival. Thus came about cheap print, serialised fiction, and an expanding entertainment economy, which created larger-than-life worlds for people struggling through daily precarity. It was in this environment that Asrar Ahmad — better known as Ibne Safi — emerged as one of the most widely read writers in the Urdu language. His popularity is often described as a matter of talent alone. Certainly, he was a gifted stylist and storyteller. But literary brilliance does not, by itself, create a readership measured in the millions. Ibne Safi’s success partially rested on a deeper foundation: a whole publishing world that stretched back to colonial North India, reshaped in post-Partition Karachi, and oriented toward cultivating habits of regular reading, lawful conduct, and modern citizenship — ideals closely aligned with the nation’s aspirations at the time. Seen this way, Ibne Safi was not merely writing spy stories; he was participating in the construction of a cultural market, and more importantly, a moral and civic imagination. Building readers, not just writing books One of the clearest signs that Ibne Safi wasn’t just spinning yarns comes from his paish lafz (prefaces). Addressing readers directly, he reassured newcomers that each novel in Jasusi Duniya was “complete” in itself, so that “new readers can start from any number without difficulty”. At the same time, he urged regular readers to place advance orders through local agents, warning that waiting until publication day might mean missing out altogether. This was not an incidental authorial chatter, but rather a market discipline. By emphasising advance orders and serial continuity, Ibne Safi helped cultivate what economists would later call “repeat demand”. Readers learned to anticipate release dates, plan purchases, and treat fiction as a regular part of monthly life rather than an occasional indulgence. These practices did not originate in Karachi. As literary historian Francesca Orsini argues , commercial Urdu publishing had already taken shape in late-colonial North India, where detective and mystery novels functioned as a full-fledged industry, complete with distribution networks, advertising strategies, and readers trained to expect regular instalments. What Karachi inherited, then, was not simply a genre but a set of practices for producing readers on a large scale. What changed after Partition was the setting in which those practices now operated. The city as mystery With a mass readership, the question was no longer just about selling books, but about what those books helped people see . Here, spy fiction drew on a much older literary move in Urdu popular writing: the transformation of everyday urban life into a spectacle. Writing about the late nineteenth century, literary scholar C. M. Naim traces how mistriz (mystery) and asrār (secret) novels began attaching suspense to recognisable places — Mistriz of Rawalpindi , Mistriz of Peshawar , Mistriz of Multan — so that readers could experience the thrill of danger not in some distant fantasy world, but in streets and cities that sounded real. That place-binding move, Naim suggests, produced what he calls a distinctly “sensational” atmosphere, where the everyday could be re-read as intrigue and risk rather than routine. Francesca Orsini takes it a step further. She argues that this kind of storytelling wasn’t just about books — it was part of a bigger entertainment wave. Theatre, music, cinema — everything was about spectacle, suspense, and novelty. Audiences were being trained to seek spectacle, suspense, and novelty as part of modern city life. In other words, “sensational” reading was not just a literary taste; it was a social habit cultivated across multiple leisure industries. Fast forward to Karachi of the 1950s, when those habits found a new metropolis, a new marketplace big enough to scale them. Pakistan’s film industry expanded rapidly — Urdu films released each year rose from five in 1949 to around 40 by 1960, per the Pakistan Film Magazine. Karachi’s entertainment economy was thriving, not only through cinema halls but also through the commercial ecosystems surrounding them. It is telling, for instance, that Ibne Safi’s early publications were sent for sale to Regal Bookstore near Regal Cinema, linking the act of buying a spy novel to the city’s most visible engine of mass spectacle. Even the material form of these books moved in the same direction: publishers increasingly adopted colored cover designs. Ibne Safi’s covers became famous for their provocative, highly “sensational” imagery, featuring mysterious scenes, violent crimes, and often Western-looking femme-fatale figures that promised danger before a reader even turned the first page. Seen this way, Ibne Safi’s fiction was not simply escapist reading that coincidentally became popular alongside films; it was part of a larger cultural production process — one that turned everyday experiences into commodities and trained readers to see the city as a legible field of secrets. His novels reimagined streets, offices, hotels, and clubs as places where plots could be hiding in plain sight. Karachi itself became a readable mystery. And maybe that’s why these stories felt so comforting back then. Karachi was growing fast — it was chaotic, unfamiliar, a little unstable. But in Safi’s world, no matter how messy things got, someone could always figure it out. The answer was never magic — it was logic. Investigation, clues, and a sharp mind could bring order. The thrill wasn’t just the danger — it was the idea that even in the chaos of modern life, things could still make sense. Language, legality, and literacy In Pakistan’s nascent years, this was no small ambition. Independence coincided with the rapid expansion of centralised state power. Yet, legality itself remained fragile. Emergency powers, crimes, and coups meant that the law was present as an ideal and absent in practice. It was precisely in this gap between law as promise and law as practice that detective fiction found its audience. Millions of readers encountered ideas about legality, evidence, and accountability not through courts or textbooks, but through popular novels sold at bookstalls and circulated through libraries. Spy fiction offered what might be called a vernacular legal education: it normalised investigation over vengeance, procedure over impulse, and reason over rumour. However spectacular the crime, Ibne Safi’s stories insisted on one thing: justice must be explained. Critics have long noted this pattern. For example, literary scholar Christina Oesterheld argues that even when Ibne Safi wrote about state-level corruption, international crime syndicates, or criminalised institutions, his stories invariably resolved through logic rather than miracle. Disorder was never left mysterious. The pleasure lay not only in suspense, but in seeing chaos rendered intelligible. Safi wasn’t shy about pushing proper Urdu either. He took the language seriously, sometimes almost too seriously. In one didactic piece, he joked that “those who did not know Urdu grammar were effectively blind, deaf, and crippled”. Hyperbole aside, the point aligned neatly with official thinking of the period. From the 1950s onward, Pakistani policymakers — often working with international organisations — treated literacy not merely as a cultural good, but as a developmental necessity. “New literates” were expected to acquire not just reading skills, but disciplined habits: regular reading, library use, and linguistic standardisation. Unesco reports from Karachi made this goal explicit. The challenge, they argued, was not teaching people to read once, but producing attractive material that would sustain reading over time. Cheap, serial, and engaging, popular fiction was perfectly suited to that task. It cultivated reading as a routine rather than an obligation. Whether or not he meant to, Safi’s novels were doing quiet, meaningful developmental work. By making legality intelligible and reading habitual, his fiction reinforced the period’s development ethos. A rupee well spent Safi knew what he was doing — and he was proud of it. He often bragged that almost every Urdu reader in both Pakistan and India knew Jasusi Duniya , and that “in today’s world, there is no other language offering such interesting literature at such a low price”. For him, literary achievement rested on three things at once: reach, quality, and accessibility. That claim was not mere self-promotion. It reflected the material realities of Karachi’s publishing market in the 1950s. Evidence from Pakistan’s National Bibliography shows that most books published by major houses during the first decade after independence were expensive — often priced well above one rupee. In a city flooded with refugees struggling to secure housing and basic necessities, such books were luxuries. But Ibne Safi’s novels were consistently priced at around Rs1, even as page counts increased. In a market where price alone could determine whether a book was read or ignored, this difference mattered. The structure of the industry helps explain why. A government report from the 1960s noted that Pakistan’s publishing sector remained small due to low literacy and weak purchasing power. To survive, publishers typically priced books at nearly three times their production cost, relying on high margins rather than high volume. Unsurprisingly, many gravitated toward textbook publishing, where demand was guaranteed by schools and state curricula. By 1960, roughly four-fifths of publishers and booksellers were involved in textbooks. Ibne Safi, however, operated differently. As both author and publisher, he was not competing head-to-head with major literary houses, nor was he dependent on institutional buyers. His business model rested on scale: large readerships, quick turnover, and modest margins. Booksellers often marked up his novels precisely because demand was so strong. Affordability was not a by-product of popularity — it was a precondition for it. The pattern becomes even clearer when looking across the broader market. Data on nearly two thousand literary titles published in West Pakistan between 1947 and 1961 reveal two consistent tendencies: first, books written in Urdu were significantly cheaper than books in other languages, and second, fiction was cheaper than non-fiction. That sweet spot — Urdu fiction — was where affordability and entertainment met. It’s no wonder it took off the way it did. This pricing structure was not accidental. Urdu was being promoted as the national language for political and administrative efficiency, while popular culture — films, chapbooks, serialised novels — was increasingly organised around sensation and entertainment. Fiction benefited from both trends. It could be printed cheaply, sold widely, and circulated rapidly. Affordability also depended on where and how books moved. Karachi’s publishing economy expanded rapidly during the 1950s, with capital and businesses concentrating in the city centre alongside cinemas, schools, and transport hubs. Yet official statistics tell only part of the story. A vast amount of reading material circulated through informal channels: chapbooks, pirated editions, and so-called “bazaar literature” that rarely appeared in state records. Unesco reports from the period acknowledged that these networks served as powerful mass distribution systems, drawing on older cultural traditions and dense personal ties. Ibne Safi’s novels thrived in this environment. Their popularity spread beyond formal bookstores into informal markets, sometimes without royalties or authorisation. This counterfeit impulse undoubtedly hurt the author financially, but it also expanded his readership. Stories travelled faster than contracts. For many readers, especially those at the margins of the formal economy, these cheaper or copied editions were the only way to participate in the new reading culture. Taken together, affordability and accessibility made his novels a social force, which allowed reading to become habitual rather than occasional. Students, clerks, muhajirs — people who were building new lives in a new city — found something familiar and exciting in those pages. A one-rupee book didn’t just pass the time; it created a shared experience and brought people into a common world of characters, clues, and conversation. The making of the world of espionage But beyond nostalgia, what does this tell us today? First, it reminds us that a reading public is created. They require cheap formats, predictable circulation, and deliberate cultivation of habits. Ibne Safi did not simply respond to demand; he helped create it. Second, it shows that popular culture can perform civic work. Long before governance became a buzzword, detective fiction familiarised readers with law, evidence, and accountability. This did not fix institutions, but it shaped expectations about how authority ought to function. Third, it highlights the political economy of language. Urdu’s centrality to Pakistan’s cultural life was reinforced not only by ideology, but by pricing, accessibility, and market scale. Finally, it poses an uncomfortable question for the present. As reading shifts from shared print cultures to fragmented digital feeds, what happens to the common habits that once anchored public life? The Unesco language of “new literates” may sound dated, but the underlying concern remains urgent: if reading becomes a luxury, civic imagination shrinks. Ibne Safi’s spies lived in the streets of Karachi because his readers did too. His stories offered a way to navigate modernity — its dangers, its rules, its promises — at a price ordinary people could afford.