Inside the Life of India’s Snakeman, Padma Shri Romulus Whitaker

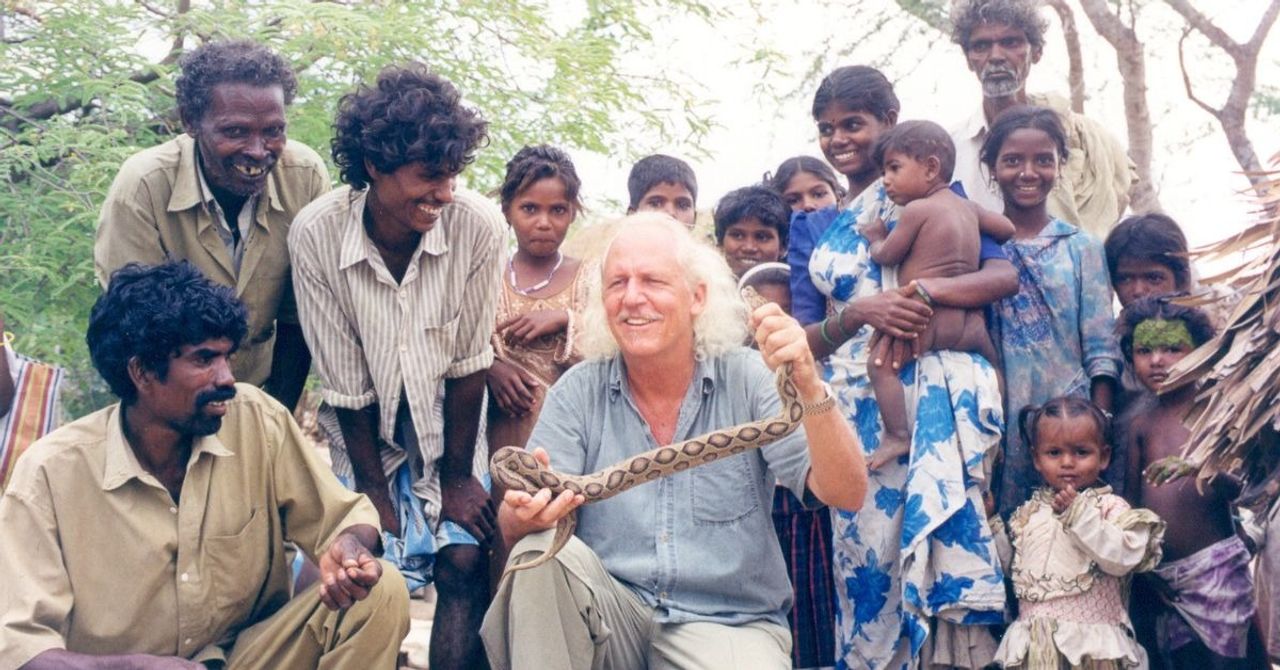

As a child, Romulus Whitaker enjoyed watching black and red ants through a magnifying glass. The innocent pastime layered his insights into their world: their little wars over bits of sugar, their tiny negotiations, and their arrival at a consensus. Years later, as he ventured deep into the wild — rescuing snakes, setting up the Madras Snake Park in 1969, the Madras Crocodile Bank Trust & Centre for Herpetology in 1976, and the Agumbe Rainforest Research Station (ARRS) in Karnataka in 2005 using his Whitley Award grant — Whitaker found himself well prepared for the quiet complexity of nature. His work would go on to focus deeply on rainforest biodiversity , particularly the elusive king cobra. Romulus Whitaker with a male gharial at Madras Crocodile Bank. Photograph: (Saravanakumar) In a chat with The Better India , this ‘Snakeman of India’, a moniker that has followed him closely, looks back on past decades and his deep fascination for snakes that hasn’t dimmed one bit. Herpetologists hail him as a bonified genius for his bond with the reptiles, and, as we learn, the roots of this love lie in an innocent story from his childhood. ‘The day I brought home a snake’ ‘Promise me you won’t kill a snake’, Whitaker’s mother chided him the day he returned home with a dead garter snake. “I was four years old at the time, but still remember how sad it made her,” Whitaker explains, adding that he had no role to play in the deed; it was his bunch of mischievous friends. But he admits he hadn’t done much to stop them. To make up for his mistake, the next time around, he brought home a snake that was alive. “The look of approval on her (his mother’s) face and her reaction — ‘It’s such a gorgeous creature’ — was enough to captivate me,” he shares. Even now, at 82, the moral heart of this Padma Shri awardee’s work lies in a deep awe and respect for the reptile . In his latest book, Snakes, Drugs and Rock 'n' Roll: My Early Years (2024) , which Whitaker has co-authored with his journalist wife Janaki Lenin, he recounts how his mother’s encouragement towards the reptile fuelled his own. (L): A young Whitaker with a milksnake, (R): An adolescent Whitaker with indigo snakes. Photograph: ((L): Doris Norden, (R): Heyward Clamp) He writes, “After that episode, I took to turning over every stone-not for earthworms but for snakes.” He goes on to describe the snakes he caught: milksnakes (that the village kids called checkered adders), tiny, delicate ring-necked snakes, De Kay's brown snake, and ribbon snakes. “Mummy helped me convert an old aquarium into a terrarium in which to keep snakes as pets. To feed them, I caught grasshoppers and small frogs in the fields,” the book notes. Years later, this love for snakes calcified into an idea for the Madras Snake Park. As Whitaker explains that plan, “While I knew how scared people are of snakes, I also knew that their interest in the reptiles supersedes their fear. My mission was to create a space where people could come, see, and learn about snakes .” Started in 1969 on the outskirts of Chennai with an admission fee of 25 paise, the park — the country’s first of its kind — moved in 1972 to the Guindy National Park campus. The Forest Department leased a parcel of land there to Whitaker, where the park found a permanent home. Today, it reportedly houses 20 species of Indian snakes, three species of Indian crocodilians, two species of exotic crocodiles, three species of Indian turtles and tortoises, four species of Indian lizards, and four species of exotic reptiles — including iguanas, slider turtles, spitting cobras, and albino pythons. Whitaker extracting cobra venom at the Madras Snake Park. Photograph: (Nina Menon) In the park’s early days, its inmates were the snakes Whitaker rescued. And there were many of them; after all, as he writes in his book, he was the neighbourhood’s “self-styled pest controller” hired to catch rats and snakes. His mother would never discourage these unusual passions. “My mother was different; she was interested in creatures of all sizes and shapes, and wonderfully encouraging of everything I did,” he shares. His life has been itinerant, coloured with experiences across the world. American-born Whitaker completed his schooling in Kodaikanal, learned about venom collection in the United States from the famous Bill Haast, owner of Miami Serpentarium, and travelled to Papua New Guinea, Mozambique, Malaysia, Bangladesh, and Indonesia as a wildlife consultant on various projects. A 16-foot Burmese python caught by the Irula tribe. Photograph: (Janaki Lenin) The multi-hyphenate has produced over 25 documentaries (including the Emmy-award-winning King Cobra (1997) ), authored six books, and was named vice-chairman of the IUCN Species Survival Commission Crocodile Specialist Group (1989-2004). But despite these iconic accolades decorating his life’s archives, Whitaker’s happiness lay in channelling his skills and repute towards social good. Empowering the Irula tribe to mend their ways In 2019, the World Health Organisation (WHO) pledged to halve snakebite deaths and related injuries by 2030. One of the biggest hurdles in achieving this goal, they stated, is effective snakebite management. (L): Whitaker with Bill Haast, (R): Whitaker with Russell's viper and the Irula tribe Photograph: ((L): Heyward Clamp, (R): Janaki Lenin) At the heart of this effort lies antivenom. Much of Romulus Whitaker’s career has been devoted to understanding venom collection , a skill he learned from his guru, Bill Haast — famed for performing live venom extractions. Haast famously immunised himself over years by injecting diluted doses of snake venom. As Whitaker worked to deepen his understanding of antivenom to save lives — even as WHO reports estimate that 81,410 to 137,880 people die annually from snakebites, with nearly three times as many suffering amputations and other permanent disabilities — his mission remained twofold: to reduce human fatalities while protecting the reptiles themselves. We turn our gaze to the story of Whitaker starting the Irula Snake Catchers’ Co-operative. In an article that Janaki Lenin authored for Sanctuary Asia magazine, she glosses over the tribe’s history. “At the [snakeskin] industry’s peak, in 1966, 25,000 snake skins were processed countrywide every day. In an average year, it was still about 17,000 skins per day. So every year, for probably 50 years, six million snakes were being killed for watch straps, belts, shoes, and handbags. The Irulas (one of India’s oldest indigenous communities) were the largest suppliers of skins.” The Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972, put the Irula tribe out of business. Whitaker, who had grown to be friends with them (united by a shared interest in the reptile), had grown to admire their knowledge of snakes . “They had become my peer group and partners,” he shares. “Once they stopped being able to sell snakes, they began starving; they were in a bad shape.” As much as he wanted to help his ‘friends’, he didn’t want it to be at the expense of the snakes, and so in a bid to facilitate an eco-mutual future for both, Whitaker came up with the idea of the co-operative, which won him his first Rolex Award for Enterprise in 1984. Romulus Whitaker with a chameleon. Photograph: (Janaki Lenin) He won his second Rolex Award for Enterprise in 2008 for his project hinged on linking India’s remaining rainforest strongholds and highlighting how their water systems sustain hundreds of millions of people across the country. To add to these accolades, two snake species have also been named after Whitaker: an Indian boa Eryx whitakeri , and a krait Bungarus romulusi . In 1982, the Irulas were issued a license to catch the big four venomous snakes — cobras, kraits, Russell’s vipers, and saw-scaled vipers. They would extract venom to sell. While their knack for catching snakes helped them do this, Whitaker reasons the work wasn’t without its dangers. “Many members have died from snake bites, because the antivenom is available in hospitals that are quite far from them.” But they persist, contributing to 80 percent of India’s antivenom. Disclaimer: Do not try this at home This story wouldn’t be what it is without a crazy anecdote that encapsulates the lengths to which Whitaker would go for his love of snakes. It’s one from the years he spent in boarding school with a pet python under his bed. “My mother’s friend bought it for me from Bombay’s Crawford Market; it was a gift. I used to carry it back home in my bag while I travelled by train. No one ever knew except my roommate and my mother.” (L): Whitaker with cobras at the Madras Snake Park, (R): Whitaker with a rescued king cobra Photograph: ((L): Linda Ballou, (R): Cedric Bregnard) His memories of snakes are vivid, embedded in muscle and instinct. He never feared the wild, he says. But call him a conservationist , and he’s insistent that’s a label others have bestowed upon him. He writes in his book, “I’ve always done what I loved, whether fishing, hunting, catching snakes, or championing the cause of habitat protection and protecting snakes. This was who I was, and still am to a large extent ― contradictions, complexities and all.” You can find Whitaker’s latest book here . All pictures courtesy Romulus Whitaker Sources 'At 81, Romulus Whitaker’s still that wild thing' : by Radhika Iyengar, 28 March 2025. 'Venomous snakebites: Exploring social barriers and opportunities for the adoption of prevention measures' , Published in Conservation Science and Practice in January 2024. 'Irulas: The Snake Trackers' : by Janaki Lenin, Published in August 2003. 'WHO launches global strategy for prevention and control of snakebite envenoming' : by World Health Organisation, Published on 23 May 2019. 'Slip sliding away: venom extraction in Tamil Nadu' : by Geetha Srimathi, Published on 27 November 2023. 'Romulus Whitaker: A Life Less Ordinary' : by Roundglass Sustain, Published on 28 July 2025.