Acura Drops Current RDX, But Teases New Model That Won’t Arrive For Years

The current Acura RDX is ending soon, and while a sleeker hybrid model is coming, buyers will have to wait a few years for its debut

The current Acura RDX is ending soon, and while a sleeker hybrid model is coming, buyers will have to wait a few years for its debut

The revived Prelude is off to a slow start in America, but targeted annual sales suggest it could soon rival the Subaru BRZ in volume

Honda wants to make camping more accessible and enjoyable for American families.

From this month, prices for over 6,000 Ford parts will be cut by 25 per cent, potentially saving owners hundreds of pounds

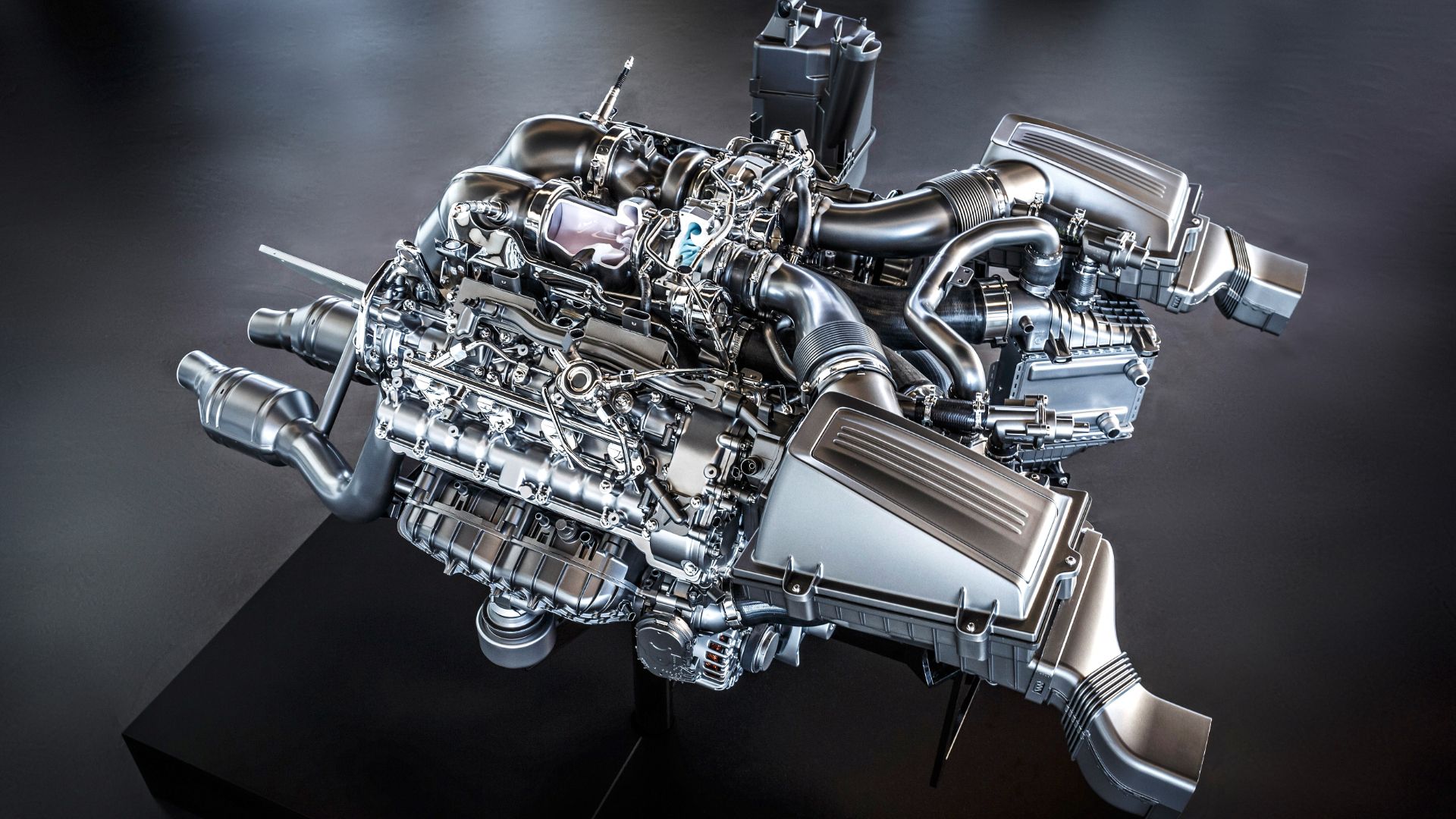

Mercedes will soon facelift the S-Class, and a report indicates that the automaker's new flat-plane crank V8 will be among the updates.

Already anonymous when it launched, does super-clean condition leave this barebones Ford deserving of a hefty price tag today?

Five Broncos with drones and Starlink are being donated to search and rescue teams, but only qualifying organizations with law enforcement backing can apply

Overlook the weak pure-petrol model and you’ll find the Chery Tiggo 8 is a supremely capable and attractively priced plug-in hybrid

Pictures of the Chery Tiggo 8 being tested on UK roads. Pictures taken by Auto Express photographer Otis Clay and Chery UK

Ford is bringing its brand of desert-bashing off-roader to more people with the more affordable RTR

Images of the new Ford Bronco RTR

Ninth model from Chinese car maker will offer up to 53 miles of engine-off range BYD will undercut the Kia Sportage and Ford Kuga with a new plug-in hybrid SUV called the Sea Lion 5, available to order now from just under £30,000. The Sea Lion 5 is BYD's ninth cars in the UK, and its fourth PHEV, joining the technically related Seal-U, Seal 6 and Atto 2 'DM-i'. Measuring 4.74m long – putting it about halfway between the Kia Sportage and Sorento, for reference – the Sealion 5 is equipped with a PHEV powertrain which combines a 1.5-litre petrol engine with an EV motor for 215bhp and a 0-62mph time of as little as 7.7 seconds. Electric energy is stored in either a 13kWh or 18.3kWh battery, the latter of which is good for 53 miles of EV range, and helps the SUV achieve 134.5mpg and combined CO2 emissions of just 48g/km on the WLTP cycle. It's available in two trims: entry-level Comfort, at £29,995, includes vegan leather upholster, a 12.8in rotating touchscreen, smartphone mirroring, six-way adjustable driver's seat and a rear-view camera. Top-spec Design trim – with the largest available battery – adds £3000 and brings welcome lights, an electric boot lid, front parking sensors, a 360deg camera, wireless phone charger and heated front seats. The first cars are due in UK showrooms from 7 February, with customer deliveries to begin shortly after.

Trump touted his openness to Chinese automakers in the U.S. as they eye the American market. The post ‘Let China Come In’ to US Auto Industry Trump Says While in Detroit: TDS appeared first on The Drive .

Dacia’s second budget EV will be built in Europe, offering an alternative to Chinese imports with unique styling, local incentives, and a compact electric drivetrain

A New Jensen inspired by the old Interceptor will arrive in 2027 with a bespoke V8 engine.

The original Interceptor was a simmering blend of Italian design, English coachbuilding, and American power, and we're looking forward to the modern version.